Line Integrals

A line integral is a way to integrate a function over a line or a path, rather than an interval or a region. Critically, the integral shows that it is dependent not only on the start and end points, but also the specific path taken to get between these two points.

1. Work and Line Integrals

Recall that work is defined as the dot product between force and displacement, the amount of energy provided by the force to perform the displacement:

\[ W = \vec{F} \cdot \Delta \vec{r} \]

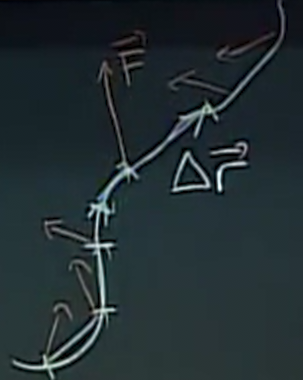

However, we may be dealing with more complicated trajectories, or when the force is not constant over the entire displacement, like so:

In these cases, we can try taking smaller and smaller segments of the trajectory and then summing all of our work calculations for each of those segments. Therefore, along some trajectory \(C\), the work adds up to the line integral:

\[ W = \lim_{\Delta r_i \to 0} \sum_i \vec{F} \cdot \Delta \vec{r_i} = \int_C \vec{F} \cdot \text{ d}\vec{r} \]

In order to actually compute this integral, we can instead integrate over time:

\begin{align} W = \int_C \vec{F} \cdot \text{ d}\vec{r} = \int_{t_1}^{t_2} \vec{F} \cdot \frac{\text{d}\vec{r}}{\text{d}t} \text{ d}t \end{align}We can also try writing the force and displacement as \(\vec{F} = \langle M, N\rangle\) and \(\text{d}\vec{r} = \langle\text{d}x, \text{ d}y\rangle\). Therefore, we have:

\begin{align} W = \int_C \vec{F} \cdot \text{ d}\vec{r} = \int_C M \text{ d}x + N \text{ d}y \end{align}Critically, note that we cannot split this into two integrals as the notation suggests, as in fact \(M\) and \(N\) depends on both \(x\) and \(y\). In order to actually evaluate this, we need to express \(M\) and \(N\) in terms of a single variable (e.g. \(t\)), and then substitute into the integral.

2. Fundamental Theorem of Calculus for Line Integrals

When our line integral is done on a gradient field, then we have a special case of the fundamental theorem of calculus. Specifically, if we have a trajectory \(C\) that runs from point \(P_0\) to point \(P_1\), then we have:

\[ \int_C \nabla f \cdot \text{ d}\vec{r} = f(P_1) - f(P_0) \]

In other words, the line integral of the gradient of a function gives you back that function. Critically note that this is only true for gradient fields, and cannot be applied universally to any vector field.

To see that this is true, we can split it up into coordinate form. The gradient field can be written as \(\langle f_x, f_y \rangle\), and so by the total differential, we have:

\[ \int_C \nabla f \cdot \text{ d}\vec{r} = \int_C f_x\text{ d}x + f_y\text{ d}y = \int_C \text{d}f = f(P_1) - f(P_0) \]

This can make the calculation of many line integrals much easier. For example, if we have the line integral of a particular vector field, as long as we can find a function \(f\) for which the vector field is \(\nabla f\), then all we need to do is to calculate the values of \(f\) at the endpoints of the curve.

The consequences of this theorem, such as this trick, is known as conservative fields and path independence. To summarize, we have four equivalent properties:

- \(\vec{F}\) is conservative

- \(\int F \cdot \text{ d}\vec{r}\) is path independent

- \(\vec{F}\) is a gradient field

- \(M \text{ d}x + N \text{ d}y = \text{d}f\)